The Core

Elements of

Typography

Design

Essential concepts for strong typographic design

Introduction to Typography

Typography is the art and technique of arranging type to make written language legible, readable, and visually appealing. It plays a key role in how we communicate through design, making it essential in graphic design, advertising, web design, and more. Understanding the basics of typography helps create effective, functional, and aesthetically pleasing designs, guiding viewers’ attention and enhancing the overall user experience.

the typographic collection

-

-

-

type Basics

Typefaces & Fonts

Anatomy of Type

Typeface

Classification

Type Size and Spacing

Type Size and Spacing

Typeface refers to the design of the letters, numbers, and symbols that make up a particular style. It includes all weights (light, bold, etc.) and variations (italic, condensed, etc.) within the design.

Font refers to a specific version or style of a typeface. For example, Helvetica is a typeface, while Helvetica Bold is a font.

Every letter in a typeface is made up of several parts. Understanding the anatomy of type helps designers choose the right typefaces and manipulate them correctly:

Typefaces are often categorized based on their design characteristics. Understanding these categories helps choose the right type for a specific project:

Proper size and spacing enhance readability and balance. Adjusting kerning, tracking, and leading ensures smooth text flow, making typography clear and visually appealing.

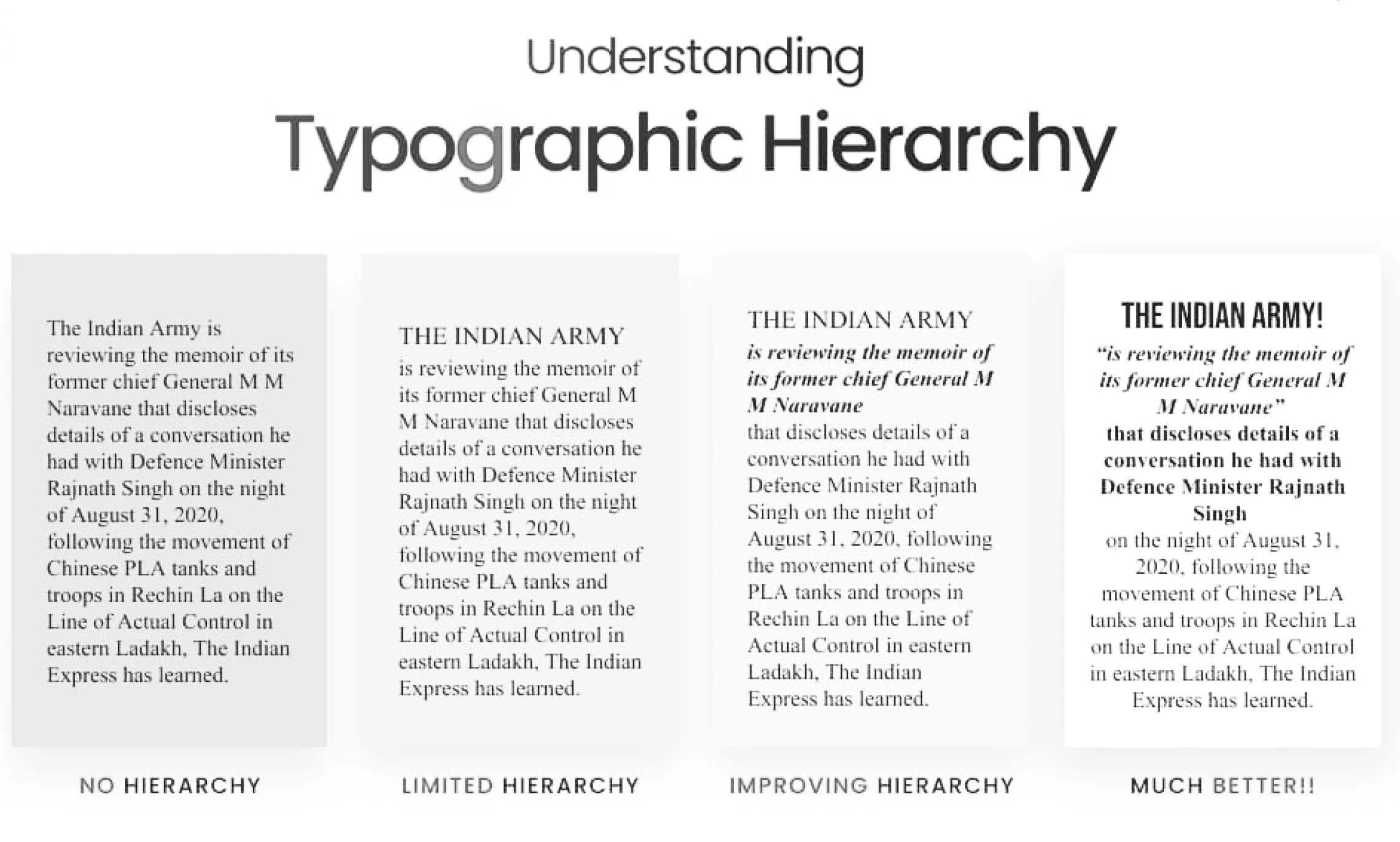

Typography hierarchy guides the reader, making key information stand out. Alignment brings structure and order, ensuring a clean, readable layout.

Explore A Top Foundry

Dive Deeper into Type Anatomy

Learn About Typography Spacing

Master Typography Hierarchy

Discover Typeface Categories

Stem

The main vertical stroke of a letter, like in "H" or "T."

Ascender

The part of a letter that extends above the height of lowercase letters (e.g., in "b" or "d").

Descender

The part of a letter that falls below the baseline (e.g., in "p" or "g").

Serif

The small projecting stroke at the end of a letter's main strokes (e.g., Times New Roman’s "T").

Bowl

The enclosed part of letters like "b," "d," or "o."

X-height

The height of the lowercase letters, specifically the height of the letter "x."

Counter

The enclosed space within letters like "o" or "e."

Terminal: The end of a stroke, especially where it doesn't have a serif (e.g., in "C" or "r").

Font Size

The size of type affects readability. In digital design, it's often measured in pixels (px), while in print, it's measured in points (pt). A good font size ensures the text is legible at the desired viewing distance.

Line Height (Leading)

The space between lines of text. This is crucial for readability—too little leading can make the text feel cramped, while too much can make the text feel disjointed. A general rule is to set the line height 1.2 to 1.5 times the font size.

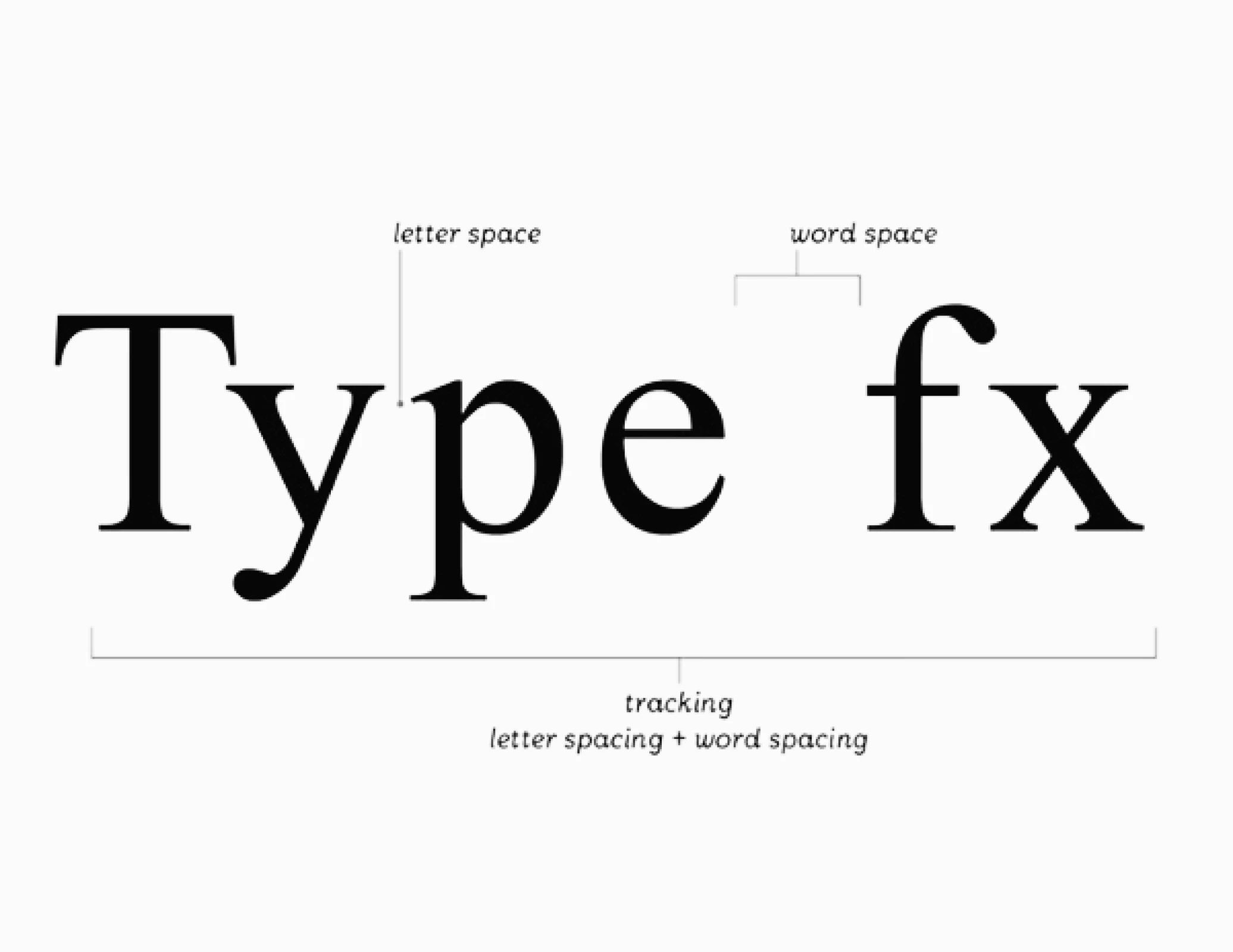

Tracking

The overall spacing between letters in a block of text. Tracking is adjusted to ensure that the text feels balanced and readable. Tight tracking can make text feel cramped, while loose tracking can make it feel airy.

Kerning

The space between individual letters. It adjusts the spacing between two specific characters to ensure consistency in appearance. Some fonts may require kerning adjustments to avoid awkward spacing.

Baseline

The line on which most letters sit. The height of letters like "x" is considered the x-height, while letters with ascenders and descenders extend above and below the baseline.

Typographical Hierarchy

Typography helps establish a visual hierarchy in design. By manipulating size, weight, and style, you can guide the reader’s eye and emphasize important information. For example, headlines are often large and bold, while body te

Alignment

The arrangement of text in relation to its container or surrounding content. Proper alignment ensures that the text is visually organized and easy to read.

Left-Aligned

The most common alignment in Western typography; it’s used for body text because it’s easy to read.

Right-Aligned

Less common but used for emphasis or specific design needs.

Centered

Often used for headlines or short blocks of

text but should be used sparingly to

maintain balance.

Justified

When the text aligns evenly along both the left and right margins, creating a clean block of text. It’s typically used for columns of body text in books and magazines but can sometimes create awkward spacing between words.

Blackletter:

Often referred to as Gothic or Old English, Blackletter fonts are characterized by their intricate, decorative strokes. These typefaces were commonly used in medieval manuscripts and early printed works. The style is dense and has sharp, angular serifs, often evoking a sense of historical tradition and authority.

Old Style

Old Style typefaces have a humanist influence with softer, rounded serifs, often evoking the feel of early printing. These fonts were designed to mimic the classic Roman letterforms, with a contrast between thick and thin strokes that create a natural, organic flow. Old Style fonts are typically used for body text in books and printed materials.

Script

Script typefaces mimic cursive or handwritten writing, with fluid, connected strokes. These fonts are often used for invitations, formal documents, and to convey a sense of elegance or personal touch. They range from elegant calligraphy-style scripts to more casual, handwritten styles.

Transitional

Transitional typefaces mark a shift between Old Style and Modern typefaces. They maintain the moderate contrast between thick and thin strokes but introduce more refined serifs and a more vertical stress. This category emerged in the 18th century and bridges the gap between classic and more modern type designs.

Modern

Modern typefaces (also known as Didone) feature extreme contrast between thick and thin strokes, with vertical serifs. They are sleek, geometric, and often have a high contrast in letterforms, making them ideal for larger text and display purposes. Modern typefaces convey a sense of sophistication and are often used in editorial and advertising designs.

Egyptian (Slab Serif)

Egyptian typefaces, often called slab serifs, are characterized by thick, block-like serifs with minimal contrast between thick and thin strokes. These fonts have a bold, sturdy look and are commonly used for headlines and branding, where a strong presence is needed.

Mono-weight

Mono-weight typefaces have uniform stroke widths with little to no contrast between thick and thin parts. This classification is often used in more modern or minimalist designs and is ideal for projects where readability and a clean aesthetic are essential. These typefaces are also common in digital design and technology-related applications.

© 1998 – 2025 typographic collection

Instagram Facebook Twitter

Designed to inform, built to inspire—explore the world of typography.

home

timeline

digital type

type basics

type & culture

type lab

type in motion

the typographic collection